AFRICAN AMERICAN MONTH has started. Let's celebrate the Black heritage of America together

Wedgwood’s slave emblem, circulation and African American visibility

Riviere Nastasia

PHD student, Rutgers University, NJ

DO

YOU FOLLOW?[1]

Wedgwood’s slave emblem, circulation and African American visibility

This paper will address the ways in which

mobility of an image lead to new meanings. It will examine the circulation of

the iconic image “Am I not a man and a brother” from its production to its

contemporary use and displays. Although the “slave medallion” is said to be the

most famous image of a black person and the most identifiable image of the abolitionist

movement there is in fact only a small body of literature relating to it. By

exploring the image’s history of circulation, this study intends to shed light

on the various meanings of this image through times and places.

From the standpoint that ‘no visible image reached us

unmediated’ (Belting, 2005: 304), this study explores how location and

relocation affect the meaning of a picture. That is to say that by taking heed

of the material and institutional dimensions of the circulation of images[2], this

research will look at how circulation and the mechanisms or agents of transportation impact the reception, consommation,

use or resistance to an image. It will demonstrate how the channels or networks

of distribution have significant effects on the visualization of an image. Drawing

on Hans Belting’s claim that « images do not exist by themselves, but they happen; they take place

whether they are moving images (where this is so obvious) or not. They happen

through transmission and perception » (2005 : 302) our approach will

be centered on the image itself and its history of circulation, rather than

from the point of view of its producers or audiences. To use the visual expression of J.T

Mitchell, images « have legs, that is, they have a surprising capacity to

generate new directions… » (1996 : 73). Therefore, this study will

retrace the hectic life of the iconic slave emblem in order to grasp the image

in its rich spectrum of meanings and purposes. This line of inquiry implies a

shift from standard methods of image’s analysis as approached by the traditionalist art history discipline. For

this reason, widening the critical look at images, this paper is methodologically

reliant on poststructuralism and on the discipline of visual culture.

Consequently, convinced that in our increasing interconnected globalized world

it is imperative to consider the implication of movement, circulation and

transport in the study of an image, this paper will re-contextualize the slave

emblem in regard to its different locations. Firstly, we will analyze

the slave emblem in its context of creation. Secondly, this study will discuss

the dissemination of this image as it became an icon and how both its representation and significances were altered through reproductions. As a

result, we will see that the slave emblem became a contested symbol within the

African-American community. Thirdly, we will show how the original design has

lost some of its part in its translation as it was being repossessed by African

American individuals.

The Am I not a man and a Brother?

image is formed by a picture and a text. Consequently, the study of the

dissemination of this image will consider the relation between the image, text

and ideology. Indeed, it will be argued that the image functions as a

discourse, which meanings are fluid and are always negotiated and renegotiated,

through its diverse spatial and temporal locations, but also through the

ideological force in which the image as discourse is used or reproduced. Moreover,

it will also analyze what happens when the image is cut off from its text, and

how the text has been re-used independently from the picture. Considering the “Am I not A Man…” image as an

icon, we will address it as an” emptied form” that is not static, but rather revised, reconstructed and refilled

depending of the context the image is used for. We argue that images are embedded

in particular histories as they constitute powerful tools of propaganda to

support the dominant ideology in which they are created.

[1] Do you follow? Art in circulation

was the title of a 2014 exhibition created by

the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) of London

[2] In Kamila Benayada et François Brunet,

« Histoire de l’art et Visual Culture aux États-Unis : quelle

pertinence pour les études de civilisation ? », Revue Française

d’Études Américaines, n°109, septembre 2006, 50.

Description

The slave

emblem represents a nude black figure with his midsections covered by a white

fabric. As a result, his body muscle is emphasized. His musculature functions

as a visual proof of his social status, he does manual labor. Hands and feet

enchained, he is depicted as a slave, kneeling with one knee on the ground,

with his arm lifted up to the sky in prayers or in a supplicant gesture. He is

not represented as foolish or threatening opposing rampant depictions of black

figures at that time. His head is looking upwards as if he was seeking the

mercy of God or Christian followers on earth. His left foot is slightly curved

as to indicate he is ready to go. This gives a dynamic to the picture and this

element juxtaposed to his musculature demonstrate that the black man has some

agency and is not lazy. Moreover, the black figure draws on antique forms (even

though there is only few kneeling figures in antiquity, the graceful

composition, the drapery and the clear musculature suggest an antique model

(Hamilton, 2013: 638), it is thus enforced with the superiority, grace and

idealized beauty granted to classic models. Cynthia S. Hamilton argues that

Wedgwood’s black figure is indebted to Hercules as he was known as the ‘kneeler’

in astronomy and she remarks that he was also represented with developed muscles

connected to his forced labor. The association with the classical figure of Hercules

brings virtue, strength and agency to the slave figure. In addition, at the

bottom of his figure runs a caption with the inscription ‘Am I not a man and a

brother’. This text is constructed as a question with the inversion verb

subject and the question mark as punctuation. Therefore it implies that this man

is addressing someone. Therefore, even though he shows agency in uttering

words, the fact that he is asking for his freedom in contrast with a person who

will affirm his rights to freedom or take his freedom, the black figure here is

still represented as a patient questioner, docile and dominated waiting to be

offered liberation from his master (God or Christians). While the picture of

this black figure gave a visibility to Blacks during the slavery period, counterattacking

the paucity of positive images of Blacks, the text provides them with a voice,

which the Black man was usually deprived of. Since the voice is often perceived

as the mirror of the thought and of the soul, two elements Blacks were said to

be deficient of, this image restores and rehabilitates his identity with

humanity. Used to create empathy in its beholder, the image will also raise

controversy as it shifted from being viewed as a statement of equality in

humanity to the lamentation of a supplicant.

Visual culture and popular politics: the Creation of the

slave medallion and the Abolitionist movement

The “Am I not a man and brother” design was not

created in the United States as it is frequently assumed. Indeed, it was

created in England by the London Committee of the Society for Effecting the

Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST). SEATS’s mission was to inform people

about the ill-treatment of enslaved African and to campaign against the slave

trade. To do so, they spread words of freedom and changed mainly through an

efficient network of books, pamphlets, prints and artifacts. On May 22, 1787,

the committee of the SEAST gathered to agree for the design of the seal of the

society for stamping the wax used to close envelops. Although the society was

formed by a majority of Quakers[1] who

generally despised art as a frivolous and luxurious activity, they were

convinced that such an image could have moralizing capacity. One of the

founding Fathers of SEAST’ s experience with African goods and slaves’ s

artifact is informative of how the society came to regard the visual imagery as

powerful instruments in their struggle against the slave trade. Thomas

Clarkson’s (1760-1846) visit of the Lively, an African trading ship involved in

the Transatlantic slave trade[2],

based on the North West England river The Mersey, had a powerful impact on him

that is continuously repeated in his various autobiographies. In an effort to

gather evidence of the slave trade, he visited many ports. Faced to the

beautiful goods of the Lively, he perceived the craftsmanship and skills that

were required to produce such items. He collected some of these goods believing

that these artifacts could appeal to people’s consciousness in the same way it

impacted him[3]. He carried a "box" featuring

his collection( figure 1 annex), which became an important part of his public

meetings. It was an early example of a visual aid. As a result, SEAST used the

same strategy to communicate their political ideas by creating the design of

the slave emblem on October 16, 1787 in an effort to mobilize humanitarian emotions in

the service of their moral cause. An image (figure 2) of the seal is inserted in Clarkson’s History of the Rise, Progress, and

Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade (1808: 450)

along with its description:

Yet who created the

design and what visual sources they consulted are nowadays unknown. SEAST then

commissioned the Wedgwood’s factory to realize a cameo of the design, and by

the end of the year Frederick William Hackwood, a modeler for the Etruria

factory, finished the cameo. Cameos were already fashionable consumer goods;

therefore it was judged adequate to publicize the movement. Josiah Wedgwood (1730-1795),

a prominent abolitionist was also a member of the Society, and a famous skillful

pottery designer (he was even appointed the Queen’s potter[1]).

Wedgwood played a central place in the dissemination of the slave emblem.

Indeed, a philanthropist, Wedgwood covered the cost of production and

distribution of the medallion. Moreover, he was significantly instrumental in

the distribution of this symbolically charged symbol when he created a whole

merchandizing circuit around the design, reproducing it on china jasperware,

enamels, tea caddie, plates, boxes…(figure 3). This constitutes an early

example of what we now call cross media marketing or again a marketing tie-in. Furthermore,

Wedgwood marketed the slave emblem through Wedgwood’ trade catalogues, “showrooms,

and his small team of travelling salesmen” (156). Yet, the ‘Slave Medallion’

seems to be an early example of what Arvidsson (2008) term as ‘ethical

economy,’ an economic system where moral values (instead of current capitalist

profit) lead the production of material goods.

Also, Wedgwood offered to pay for an illustration

of the kneeling slave to adorn the title page of William Fox[1]’s

An Address to the People of Great Britain,

on the Utility of Refraining from the Use of West India Sugar and Rum

(1792). In less than a year,

Fox’s Address became the most widely circulated pamphlet of the

eighteenth century with more than 200,000 copies distributed in Great Britain

and America (Jennings, 2013 : 176[2]). Wedgwood is notably known today as the 19th most influential

businessman of all times (Forbes, 2005), as if he was able to transform a

common design into a very famous brand and more importantly, an object of

desire. Indeed, the slave emblem was very successful across social and

political divide. The slave emblem was an instant hit. Also, Cynthia S. Hamilton (2013) informs us that Clarkson noted that he had

received some 500 such medallions for distribution (633[3]).

As Thomas Clarkson accounts:

There were soon as the Negro’s complaint, in different parts

of the Kingdom. Some had them inlaid in gold on the lid of their snuff-boxes.

Of the ladies several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in

ornamental manner as pins for their hair»

He thus remarked:

At lenghts, the taste for wearing them became

general ; and thus fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless

things, was seen for once in the honorable office of promoting the cause of

justice, humanity and freedom ( 1808 : 154[4]).

Women, who were at

that time banned from voting, could visually voice their opinion by wearing a

slave emblem pins hair. Notwithstanding a tea set enables people to display

their convictions and beliefs, it was also a way to fashion one’s identity in solidarity

with the abolitionists rather than to take an active part in the movement. Yet, as Adam Hochschild noted, Wedgwood’s

slave emblem was « probably the first widespread use of a logo designed

for a political cause » served as the « equivalent of the label

buttons we wear for electoral campaigns » (2006 : 128[5]) ;

All in all, Wedgwood’s products were imported by lot of country, such as USA,

Germany, and France, disseminating slave’s

suffering and humanity. Moreover, In February 29, 1788, Wedgwood sent Benjamin Franklin, then

President of the Abolition Society in America, a package of his jasper cameos

and slave emblem ‘Am I not a Man and a Brother?’ and wrote:

‘I embrace the

opportunity to enclose for the use of your Excellency and friends, a few cameos

on a subject which, I am happy to acquaint you, is daily more and more taking

the possession of men's minds on this side of the Atlantic as well as with you.

It gives me a great pleasure to be embarked on this occasion in the same great

and good cause with you, Sir, and I ardently hope for the final completion of

our wishes.’

to what Franklyn replied in a

letter dated 15 May 1789:

“ I have seen in their

viewers’ countenances such mark of being affected by contemplating the figure

of the Suppliant that I am persuaded it may have an effect equal to that of he

best written pamphlet, in procuring favour to those oppressed People”.

As early than November

1788, the Connecticut newspapers the New Haven Gazette notified the public that

the ‘American Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade have the following

device for their seal – A Negro naked, bound in fetters, and kneeling in a

suppliant posture – the motto, Am I Not a Man and a Brother!’[6]

and in 1837, Wedgwood’s kneeling slave appeared on John Greenleaf Withers’s

anti-slavery poem Our

countrymen in chains. Wither was an American Quaker poet and advocate of

the abolition of slavery. On the 1837 broadside publication of the poem, we

can read that leaflets of the poem were « Sold at the Anti-Slavery

Office, 144 Nassau Street. Price TWO CENTS Single; or

$1.00 per hundred. ». The poem was therefore used as a powerful of

propaganda, appealing to the reader through the choice of words but also

through the image of the supplicant slave. Also, a note at the bottom of the

poem informs the explicited comparison establishes throughout the poem between

England kingdom and the Free United States : * ENGLAND has 800,000 Slaves,

and she has made them FREE. America has 2,250,000!—and she HOLDS THEM FAST!!!. Most

importantly, the religious reading of the image « Am I not a man » is

reinforced by the poem, where appears at the very end the quotation from the

Bible: “ He that stealeth a man and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand,

he shall surely be put to death (Exodus. xxi. 16)”. This association of text

with the Wedgwood’s slave emblem renders more explicit the un-christianity of

the slavery system that the original image was trying to convey. Yet, if the

design penetrated the American soil, it was not long before creating raging

debates and for active measures to curtail this surge of free speech. Indeed, the

image was deemed « incendiary » (Patton, 75). In the summer of 1835,

while antislavery partisans were organizing and distributing propagandist tracks,

including the slave emblem on them, through the mail boxes of the South, At Charleston, South Carolina, on 29 July,

a mob of three hundred citizens decided to seize the abolitionist materials and

to burn them. Correspondingly, the « mail controversy » led President

Andrew Jackson to call for a law to prohibit « under severe penalty »

the circulation of abolitionist tracks in the South[7].

However, it is significant to mention that the myriad of representations

copying Wedgwood’s black figure altered some features of the original and as a

result its significance shifted. Indeed, the slave was represented with a more

caricatured set of African features unlike the original that represented a more

universal man as to convey universal human rights. Conversely, through its

multiple reproductions, the slave emblem was being reframed as the Other. Also, his musculature was less prominent and

he is standing both on his knees which consequently, Hamilton argued, gave « him less potential to rise

unassisted » (2013 : 642). Therefore, he was being represented as a less

graceful and a less potently able being, but rather as the Other or victim in

need of rescue from the White man. As a result, the slave emblem became less an

emblem of a common humanity than an emblem for abolitionists to display their

convictions and actions and to fashion them as good believers and potent

saviors. It enabled abolitionists to affirm their own agency.

The

study of the circulation of the Wedgwood’s kneeling slave is informative of the

continuous exchange of abolitionist ideas and objects between England and the

United States, and of the role of these networks in the history of the

abolition of slavery. It is also particularly instructive of how images came to

be considered and used as a vehicle of politically charged message and as tools

to publicize the movement of abolition. Indeed, the Wedgwood’s slave emblem

became a key element in the visual vocabulary of abolition. The mobility of the

“am I not a man..” design testifies of its rousing success and in the effort to

bring awareness to the cause how abolitionist came to pick moralizing artifacts.

Yet, it is also – if not more so- a way to emphasis the role of White

abolitionist in the movement, since as we discussed, people used the emblems as

a fashion statement in support of the abolitionists. Moreover, it also reveals how the

abolitionist movement created a vast network of artistic exchanges. For

instance, American printmaker and engraver Patrick H. Reason was sponsored by

the New-York Anti-Slavery Society to study the engraving technique in London.

In 1839, on his return Reason realized a copy of Wedgwood’s slave emblem in a

copper-engraving of the same title for the Philadelphia Vigilant Committee, an

African-American benevolent organization.

The

« Am I not a man… » design persisted on the other side of the

Atlantic, where it informed representations of African-Americans. Yet, the

« kneeling slave » will run free from its inscription « am I not

a man and a brother ».

2/ Public monuments and contested visibility

The image of the slave,

hands clasped in chains, asking for freedom have a long survival through art

history and African American art history in particular. Arguably, the enduring

presence and influence of this iconography throughout the US visual culture is

another form of circulation of this image. After the civil war, the new society

recently emancipated from slavery sought to represent and/or commemorate the

peculiar institution and American freedom. They often referred to Wedgwood’s

figure in what will become the first time a black figure would appear in

national monuments. Perhaps its most famous visual manifestation is Thomas

Ball’s The Emancipation group sculpture

taking place in the Freedmen’s memorial to Abraham Lincoln. Located in Lincoln

Park, In Washington DC., the sculptural project was completed in 1876. It was financed by freed Blacks; However, it

was the « friends » of the freedmen who would determine the character

of the monument (Savage, 1999 : 92[1]).

Although the freedmen considered a visual monument addressing the freedom of

Black slaves merely as just a representation but rather as an enactment in

itself, that is to say a way to « translate into the sculptural language

of the human body principles of freedom that remained abstract and barely

imaginable » (89), the sculpture however forms an archetype of the slave

emblem, not a freed man. That is to say they modeled the structures upon the

later representation of the slave emblem rather than on Wedgwood’s original. Indeed,

the slave figure is on his knees, but totally stripped off of any individual

agency. On the contrary, Abraham Lincoln stands above him, in a paternalistic

manner. His elongated hand is placed above the slave’s docile curving back, in

an authoritative yet protective manner. Here, the slave emblem is once again

dependent of white authority, both in the realization of the sculptural

project, but also visually as a subject of Lincoln’s liberation. The slave

figure is also naked with the folds of the drapery covering his midsection, yet

there is no heroic aspect in his nudity, but rather a negation of its masculinity.

Manhood is monopolized by the white figure standing upward in its grandeur. However,

the Emancipation group sculpture

succeeded to manifest freedmen’s own civic responsibility in the creation of a

public monument, while Wedgwood’s design rested entirely on White abolitionist

avenues and networks.

Edmonia Lewis’s sculpture Forever Free (figure 7) is an earlier example of the influence

of Wedgwood’s kneeling slave in artwork related to slavery. In 1867, the first documented American sculptor

of African-Indian descent Mary Edmonia Lewis completed her marble sculpture

representing a black couple. While the man’s stance and his raised arm are

interpreted as a triumphant and protective gesture, the woman is kneeling and

begging her hand joined together. The woman figure copies a familiar

image as Sharon F. Patton remarked (2006: 95) : the women’s abolitionist

emblem which was modeled after Wedgwood’s

male slave. Indeed, women abolitionist movements also adopted Wedgwood’s emblem

to proselytize their cause by transforming the male slave into a female slave,

sometimes with the motto: « Am I not a woman and a sister? ». For

instance, The Liberator[1]

used it as a header for the ‘ Ladies’ s Department’ column( figure 8). In

addition, the design was also used to appeal to women’s rights in general, not

just the black woman. In choosing an emblem of slavery, they were expressing

the forceful view that women as a gender were also treated as slaves, as various

forms of patriarchal domination have colonized them. When women are subjected to both the “colonial”

domination of empire and the male-domination of patriarchy, we used the catchy phrase

“double colonization”. The two meaning

of the same image informed us of the various possible readings and

interpretations of Forever Free.

Indeed, many scholars have discussed the complexity of this iconography (see

Kirsten P. Buick, “The Ideal

Works of Edmonia Lewis: Invoking and Inverting Autobiography”, American Art Vol. 9, No. 2 (Summer, 1995), pp. 4-19 for

an exhaustive discussion of the various interpretations). In short, either

Lewis’s sculpture gave a visibility to the female slave ‘s struggle in slavery,

or it gage a visibility to her struggle as a subject of male’s patriarchism,

therefore the victim of both slavery and patriarchal oppression. Moreover, some

regarded the sculpture as a unit not as a group of two oppositional figures as

they remarked that Forever free

expresses visually the African-American family struggle that will face the

community after emancipation.

To

conclude, the conversation taking place between later work of art focusing on

slavery and Wedgwood’s prototype of a representation for a suppliant slave also

inform us of the circulation of an image, and how its meaning can be altered

and transformed through times and places. More recently, the circulation of the

slave emblem prototype has created discontents in the United States as some

people criticized the contemporary use and visibility of this figure in the

modern American society. Indeed, they regarded the slave emblem as a

reminder of the atrocities of American past. Also, they consider it as another

example of a White’s visual representation of a black figure where a black

person is depicted as inferior, supplicant for freedom and as a good Christian

black slave. For this reason, they judged the image pejorative and negative, and

viewed its dissemination as belonging to a racist discourse. Their reactions

offer us a rich insight into the enduring life of the slave emblem and its

lingering impacts. The way people appreciate an image through time also evokes

its circulation, as the reception of an image is channeled through times and

place, discourse and particular histories.

To

conclude, the conversation taking place between later work of art focusing on

slavery and Wedgwood’s prototype of a representation for a suppliant slave also

inform us of the circulation of an image, and how its meaning can be altered

and transformed through times and places. More recently, the circulation of the

slave emblem prototype has created discontents in the United States as some

people criticized the contemporary use and visibility of this figure in the

modern American society. Indeed, they regarded the slave emblem as a

reminder of the atrocities of American past. Also, they consider it as another

example of a White’s visual representation of a black figure where a black

person is depicted as inferior, supplicant for freedom and as a good Christian

black slave. For this reason, they judged the image pejorative and negative, and

viewed its dissemination as belonging to a racist discourse. Their reactions

offer us a rich insight into the enduring life of the slave emblem and its

lingering impacts. The way people appreciate an image through time also evokes

its circulation, as the reception of an image is channeled through times and

place, discourse and particular histories.

The unrealized project of the African

American artist Fred Wilson entitled E

Pluribus Unum indicates the recurrent problem of representing a racial

figure without conveying stereotypes. It forms an example out of many of how

the African American community feels it has the right of a larger say in the

matter of how they are represented and how their history should be represented,

even though it might be in opposition with dominant ideologies and discourse.

Fred Wilson’s project consisted of a public sculpture representing an

emancipated slave. It was to be located in downtown Indianapolis, yet the whole

project was eventually dismissed as it was faced by major protestations. Wilson’s

cultural scheme was to create a public sculpture with a black figure in it since

Wilson remarked there was only one public artwork in the whole city displaying

a black figure, namely the Soldiers and

sailors Civil war memorial group sculpture (figure 9). The sculpture was made by Rudolf Schwarz in 1902 and the black

figure shares some characteristic with Wedgwood’s slave emblem, notably he is

looking up at the allegorical female figure of freedom, raising his hand

towards her in an effort to reach her. Wilson wanted to “rework” the Schwarz’s

black figure by giving it its independence from the other characters

surrounding it and especially the allegorical figure of freedom. In a sense, Wilson’s

black figure would have looked even more as Wedgwood’s, although Wedgwood’

slave is still tied to another presence mostly because he is representing begging,

implying an interlocutor. Wilson wanted to emancipate his slave figure from any

other controlling or superior figure for the black figure to become simply: ‘ a

person, he is a man, and he can represent something else, something positive;’

His project was driven by a desire to reimagine the black figure’s identity and

to give him individuality and agency as he would have held a flag of the African diaspora.

Wilson’s unrealized project reveals potential reasons why the slave emblem came

to be less frequently appropriated as it was perceived as a negative caricature

of a victim. Indeed, Wedgwood’s black figure proved to be more difficult to

adapt to different contexts and to be re-used through time as it was regarded

as derogatory. Yet, as we will see his text « Am I not a man… » has resisted as it penetrates

various historical events, enter different locations and was appropriated by

distinct social, racial and gendered individuals. This exemplifies how through

mobility some images or some parts of an image move, adapt or stick better than

others.

3/ I AM A MAN

and the archival impulse.

The figure of

Wedgwood’s slave was not the only thing that widely circulated in the United

States. Other parts of the emblem were re-used and transformed to fit specific

contexts and narrations. Indeed, the motto “Am I not A Man and a Brother?” will

re-emerge in various contexts, independently from the figure of the black

slave. As such it is an example of how symbol, icon and myth work as blank

screen upon which discourse can project themselves, that is to say that

Wedgwood’s figure and motto serve as mute candidates for “human ventriloquism”.

By separating the image from its text, both find a new freedom and

meanings.

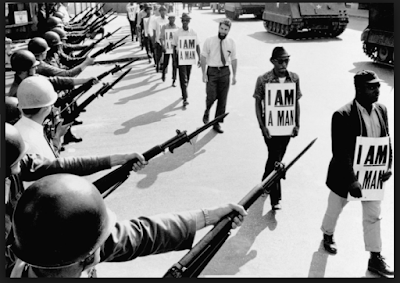

In 1968, for

instance, during the Civil Right Era, the motto coming from Wedgwood’ s slave

emblem resurfaced with a little adjustment: from “Am I not a man and a brother”

the motto became “I am a man”. As can be

seen, the motto went from a question to a statement. The 1968 motto was being

produced both orally and visually during the Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike as it was used as a sign. The

strike was captured by the Memphis-based African-American photojournalist

Ernest C. Withers (1922-2007) most famous for his visual documentation of key

historical moments of the Civil Rights movement. Memphis Sanitation workers were taking the streets to protest after

that two workers were crushed to death due to a malfunctioning truck. Using as

rallying cry the sign « I am a man » they expressed that labor rights

are also human rights. The link between Wedgwood’s motto and I am a man give an

in-depth understanding of how they regarded their situation: namely an instance

of modern- day slavery. Using this similar motto they were drawing a striking

visual and social parallel between the dehumanization of slavery and the inhuman

condition contemporary work system. Even though they did not use the figure of

the kneeling slave, the picture transcribes another black body as the producer

of the motto, the strikers. Conversely, by reusing this motto themselves, the

strikers actualized Wedgwood’s slave emblem, not only for commenting on their

actual slavery but also as a way to repossess the fight against slavery. They

are not performing as victims asking for pity as seen on later reproductions of

the slave emblem. Rather, they affirm their agency to spark a march to voice

their struggle. Displaying their physical black body instead of a

representation of a black figure seems to be a comment against visual

stereotyping and ”othering” that are inscribed in slave emblem. However, one crucial difference with

Wedgwood’s motto is the absence of the rest of the sentence: and a brother?. I

will argue that the sentence was cut off because it was not a period when

African-Americans (the majority of the striker during the Memphis strike were

African Americans) sought brotherhood with White men. Indeed, the Civil Right

period also witnessed the upsurge of Black Nationalism and other separatist

ideologies. Moreover, the verb

be is underlined visually as to meaningfully emphasize that African Americans

are not asking anyone to grant them humanity, freedom and right, but they are

rather asserting them since the verb be is one of the strongest tools of

assertion and the present tense also conveys immediacy. Therefore, it departs

significantly from Wedgwood’s original that was using a question sentence with

the subject-verb inversion and the question mark as punctuation. In addition the new motto is a subject

complement where “I” and “man” are equal and interchangeable entity, with the

verb be as a the bond between the two as an instrument of

definition. Thus, they are asserting their full membership in manhood and

humanity.

Wither’s photograph I am a man: Sanitation workers assemble in front of Clayborn Temple for

a solidarity march, Memphis, Tennessee, 1968 has now become an icon of the

Visual culture of the civil right struggle and continues to be widely spread

through a network of merchandizing, such as postcards, poster, book covers… and

other portable objects such as t-shirt or buttons that disseminates the message

I am a Man even further in the same way Wedgwood’s medallion was turned into a

fashion artifact. Moreover, Withers’ s image continues to circulate also via

cultural institutions such as Black history museums (the National Civil Rights

Museum of Memphis for instance) and special exhibitions with the Civil Right

period as a focus. For instance, the travelling exhibition For all the World to see: the Visual culture and the struggle for Civil

rights organized by the

Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture of the University of Maryland, and in

partnership with the National Museum of African American History and Culture,

Smithsonian Institution has

adopted Withier’s image as the header of its online exhibition[1]

and as a cover for its companion book (Yale university Press). The MoCADA museum

also celebrated the legacy of the iconic motto I am a Man in 2008 with a

special exhibition regrouping a dozen of artists paying homage to Withiers’ s

photograph (Sept.25, 2008- Jan. 18, 2009, curated by Kevin Powell). In

addition, during the opening weeks of the exhibition New York Times

photojournalist Chester Higgins Jr., organized a photo shout with two hundred

men wearing T-shirts emblazoned with “I Am a Man” as to recreate Withers’ s

image.

African American Glenn Ligon and

Hank Willis Thomas were some of the artists included at the MoCADA show whose

works appropriated Wither’ s iconic image. Their artistic engagement belongs to

a larger artistic practice of revision, recycling and re-appropriation of found

objects or mass popular culture images that began with cubism and was most

evident in Duchamp’s ready-made of Warhol’s Marilyn for instance. Their work

are also instances of archival

art, that is to say art that “ elaborates on the found image, object and text,

and favor the installation format” so as to “ make historical information,

often lost or displayed, physically present” (Hoster, 2004, 4). This type of appropriation of previous images is another form of

circulation of the prototype image and informs us of its social life, and how

people and artists with their own frame of reference will relate differently to

the image.

In 1988, Glenn Ligon completed his oeuvre

“untitled” ( I am a man) ( figure 12), a oil and enamel on canvas.

Consequently, the message of the Memphis strikers’ s placard is here

transported to a painting on a canvas. Re-appropriation is the touchtone of

Ligon’ s work, whose engagement with quotation, literary and discursive

production represents the core of his oeuvre. Ligon’ s Untitled feigned to be a ready-made as it shares striking

similarities with the Memphis strikers ‘s placard. Yet, by giving a rich visual

and material texture to the word Man, he represents a black body without using

figuration. By doing so, he is commenting on the social invisibility tied to

the Memphis sanitation workers and how they became visible both as Black men

and Black workers when raising the placard I am a Man during the 1968 strike.

Ligon’ s image also expresses regimes of visibility that preconditions the

visualization of black body. Indeed, his black letters are only visible because

they are thrown upon a sharp white background[1].

It is a way to discuss US cultural institutions and its networks, but also the

largest history of black figuration in the US culture with the Whites’

dominance on the definition and representation on Blacks’ identities. This work

can also be interpreted as a self-portrait, a statement f identity from Ligon.

Correspondingly, we are left to wonder who does the ‘I’ refer to? To Wedgwood’s

slave? To the Memphis strikers? Given that his work is in conversation with the

history and the circulation of the motto Am I not a man and a brother? And I am

a man, it draws on the various meanings of the uses of the motto that

ends up merged in this single canvas.

In 2009, Hank Willis Thomas widened the

possible identities which lies in the vernacular statement ‘I am a man’ by re-interpreting

the sign in a series of twenty photographs, creating a sort of timeline of the

use of the sentences through history from “I am 3/5 man , Am I a man… I am

a Man… I am Your man…Ain’t I a woman, I am a Woman, I am Human… I am Amen”.

This series condenses racial, sexual, social, political issues of identity that

are gathered in the text I am a man.

More recently, in 2012, the French street

artist JR brings to life Whitiers’ s image as he took the 14th street

in Washington D.C by covering an entire unoccupied building with Withiers’ s iconic

photograph of the Civil Rights era. His in-situ artistic performance is another

example of what scholar Hal Foster named the «

archival impulse ». He pasted a

giant single image of Withiers’ photograph in the same corner of the street

where the strike exploded, as he stated: “They created such a strong and powerful image that still resonates

today, but in another context. Still people say, ‘I am a man,’ but they care

less about the color [of their skin]. It’s ‘we are humans, we are here, we want

to exist.’ And I like that, I think that’s pretty powerful”[1]

( J.R, 2012 in the Washingtonpost).

CONCLUSION

Studying the “Am I not a man” image through

its history of circulations provides us with a rich analysis of the dynamics of

visual rhetoric. Indeed, from its context of creation, the mechanism of its

diffusion and the agents of its dissemination, discourse were brought into the

image, impacting its reception. They were discourse of dominance and hegemony

that fixed the experience of Wedgwood’s black figure into a victim. The circulation of this image also informs us

about the visibility of Black figures through times and how little by little not

only more visibility was required by African Americans but also different kind

of representations in which the African American community will be in control

of the depiction and presentation of the black figure. With this in mind, we

are offered accordingly an in-depth understanding of why people and artists

feel the need to re-appropriate the image as it is informative of why the

circulation of the image in the public society triggers some discontents.

Consequently, the study of the image’s circulation has enabled us to grasp the

varieties of meanings attached to it and the role it has plays in the

visibility of black figures. While some parts of the image were lost through

time at the advantage of others, we suggested that the separation of the text

from the image was a liberation for the survival of the image. It was reshaped

into a direct experience of black and white lettering without the derogative

representation of a black figure. Accordingly, the motto I am a man was

reshaped into a universal statement of racial, sexual and social content and

stands more in line with Wedgwood’s original.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Belting

, Hans, « Image, Medium, Body: A New Approach to

Iconology », Critical Inquiry; Winter 2005; 31, 2; ProQuest

Direct Complete

Benayada, Kamila ; Brunet, François.,

« Histoire de l’art et Visual Culture aux États-Unis : quelle

pertinence pour les études de civilisation ? », Revue Française

d’Études Américaines, n°109, septembre 2006

Bernier, Celeste Marie, Newman,

Judie., Public Art, Memorials and

Atlantic Slavery, Routledge, 2013

Clarkson, Thomas , edt by James P. Parke, The history of the rise, progress, &

accomplishment of the abolition of the African slave-trade, by the British

Parliament , No. 119, High street,

1808

Foster, Hal, « the archival impulse », October,

vol.110, Autumn 2004, the MIT PRESS

Hall, Stuart, Representation: Cultural

Representations and Signifying Practices, SAGE, 8 avr.

1997

Hamilton, Cynthia S. « Hercules Subdued: The Visual Rhetoric

of the Kneeling Slave, Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and

Post-Slave Studies », Routledge, 2013

Historicus, ‘February 5,

1788’, The New Haven Gazette, and the Connecticut Magazine,

November 13, 1788,

3, 45.

Hochschild, Adam, Bury the Chains: Prophets and

Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves, Houghton

Mifflin Harcourt, 2006

Jennings, Judith, The Business of Abolishing the

British Slave Trade, 1783-1807, Routledge, 2013

Jones,

Phillip E., Mariners, Merchants And The

Military Too, A history of the British empire,

Mercieca, Jennifer Rose, “The

Culture of Honor: How Slaveholders Responded to the Abolitionist Mail Crisis of

1835”

Mitchell, W. J. T,

What Do Pictures "Really" Want?

: October, Vol. 77, Summer,

1996, published by The MIT Press

Patton, Sharon F., African American art, Oxford University Press, 1998

Rothkopf, Scott ;

Als, Hilton ; Golden, Thelman, Glenn

Ligon: America, Whitney Museum of American Art, 2011

Savage, Kirk, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race,

War, and Monument in Nineteenth-century America Princeton

University Press, 1999

SITOGRAPHY

Official website of the African

American artist Fred Wilson: http://www.fredwilsonindy.org/

Official website of the African

American artist Hank Willis

Thomas : http://www.hankwillisthomas.com

The library

of congress: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661312/

The

exhibition for all the world to see website: http://www.umbc.edu/cadvc/foralltheworld/

[1] Maura Judkis “French artist JR covers D.C. building with

iconic photo of civil rights era » Washington

post, 2012, retrived at http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/french-artist-jr-covers-dc-building-with-iconic-photo-of-civil-rights-era/2012/10/10/8f02e080-12fd-11e2-a16b-2c110031514a_story.html

[1] He further

explored this relation in his 1990 work entitled I feel most colored when i am thrown against a shapr white background

, appropriating the famous quote of the African American writer Zora Neal

Hurson’s book How it feel to be a colored

me.

[1] The liberator ( 1831-1865) was originally an abolitionist

neswpaper and also became a woman’s rights advocators when in 1838 they

made the paper’s goal “to redeem woman as well as man from a servile to an

equal condition,” it would support “the rights of woman to their utmost

extent ».

[1] Savage, Kirk ,

Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in

Nineteenth-century Americ, a Princeton University Press, 1999

[1] http://www.brycchancarey.com/abolition/williamfox.htm, the address advocated to restrain from West Indian produce as a means

of ending the slave trade. It led to the Abstention movement.

[2] Judith Jennings , The Business of Abolishing the British Slave

Trade, 1783-1807, Routledge, 2013

[3] Cynthia S. Hamilton, « Hercules Subdued: The Visual

Rhetoric of the Kneeling Slave, Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and

Post-Slave Studies », Routledge, 2013

[4] , Thomas Clarkson , edt by James

P. Parke, The history of the rise, progress, & accomplishment of the

abolition of the African slave-trade, by the British Parliament , No. 119, High street, 1808

[5] Adam Hochschild , Bury the Chains: Prophets and

Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves, Houghton

Mifflin Harcourt, 2006

[6] Historicus, ‘February 5, 1788’, The New

Haven Gazzette, and the Connecticut Magazine,

November 13, 1788, 3, 45.

[7] Jennifer Rose Mercieca, “The

Culture of Honor: How Slaveholders Responded to the Abolitionist Mail Crisis of

1835” at https://www.academia.edu/227142/The_Culture_of_Honor_How_Slaveholders_Responded_to_the_Abolitionist_Mail_Crisis_of_1835

[1] Celeste Marie Bernier, Judie

Newman, Public Art,

Memorials and Atlantic Slavery, Routledge, 2013, p 83

Comments

Post a Comment